For centuries, paper has represented security. Contracts, deeds, and laws have relied on physical documents to ensure truth and authenticity. In many sectors, printed records still serve as reliable, tangible evidence.

Nevertheless, verifying the identities of millions in a mobile society exposes the limitations of paper-based systems. It deteriorates, is more susceptible to forgery, and does not integrate well with digital borders or automated validation.

Within the European Union, where citizenship grants the right to move, reside, and cross borders with valid documents, identification must be efficient and compatible with modern technology. The freedom of movement under EU law now demands documents that are more secure and standardised than traditional paper formats.

This shift has led to the adoption of identity cards that are more durable, technologically advanced, and aligned with international standards, such as the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO standard), thereby ensuring greater document security.

The European legal framework for standardisation

The modernisation of identity documents in Europe is not merely an aesthetic update or an isolated decision by individual countries, but the result of a common and binding framework.

National documents with lower security levels are more susceptible to forgery for travel within the European area. This weakness facilitates the abuse of free movement rights, document fraud, and risks associated with cross-border crime or terrorism.

That is why the Council of the European Union adopted Regulation (EU) 2025/1208, a directly applicable instrument that harmonises the security and format requirements of identity and residence documents. Specifically, the regulation applies to:

- Identity documents issued by countries to their own citizens (Article 4.3 of Directive 2004/38/EC): official documents, such as national identity cards or passports, that certify a citizen’s identity and nationality within the EU framework.

- Residence cards for family members of EU citizens who are not nationals of a Member State (Article 20 of Directive 2004/38/EC): documents allowing non-EU family members to reside legally in the host Member State.

- Registration certificates and documents certifying permanent residence for Union citizens living in another European country (Articles 8 and 19 of Directive 2004/38/EC): documents confirming that a citizen has registered their residence in the host country or has acquired the right of permanent residence after meeting the legal requirements.

Unlike directives, which must be transposed into national law, this Regulation does not require transposition into national law. It applies automatically and establishes identical rules and common technical standards for all Member States. Countries will therefore continue issuing their own documents, but will no longer be able to decide freely how they should be designed.

What must national identity documents in the European Union be like?

The reform defines in detail how such documents must be designed, manufactured and structured so that they can be used with the same level of trust in any European country.

Technical structure of the document

New national identity documents must adopt the ID-1 format (similar to a bank card) and use materials more durable than paper or simple laminates, such as multilayer polycarbonate. The substrate must withstand intensive use while making physical tampering or data alteration more difficult.

The nominal dimensions are 85.60 mm (3.370 in) wide × 53.98 mm (2.125 in) high.

In addition to this physical base, a common electronic architecture is required. Cards incorporate a contactless secure storage chip, biometric data in interoperable formats, and a machine-readable zone compatible with international standards. This zone encodes essential information about the holder in a structured format so it can be automatically read by verification systems in any country.

The document thus ceases to be something inspected only visually by an official or officer and instead is designed to interact with optical readers, automated controls, kiosks, eGates, and digital identity verification solutions capable of capturing and validating information within seconds.

To guarantee compatibility, the Regulation refers to established international specifications, particularly those defined by ICAO in Document 9303, Part 5, which act as a common language between physical documents and technological tools.

Common visual elements across Member States

The presentation, data layout, and the way each document is identified must follow common guidelines that facilitate both machine inspection and human review across any country. Essential information must be clearly legible, with consistent typefaces, sizes and field order, enabling a foreign officer to locate data quickly without relying on language or national design.

For this reason, the name of the document must appear in the language of the issuing State and in at least one other official EU language. Countries may retain historically established denominations, but the creation of new names that might hinder recognition is discouraged.

In addition, all national identity documents feature a common front feature: a two-letter country code printed in negative within a blue rectangle surrounded by 12 yellow stars. Far from being decorative, this symbol allows the origin of the document to be identified during cross-border checks or verifications.

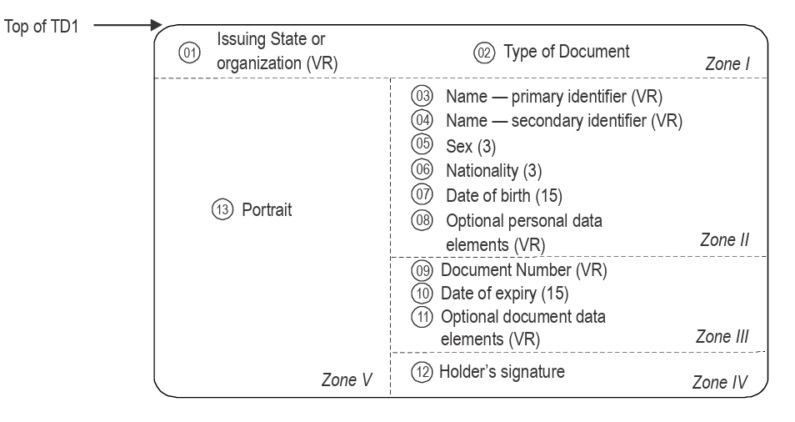

Another provision of the Regulation is that the document number may be entered in zone I, and the indication of the holder’s gender is optional.

Figure 1. Data layout on the front side

Note. Reprinted from Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs) (p. 5), by International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 2021, Doc 9303.

Member States may add their own features provided these do not reduce the effectiveness of common security measures or affect compatibility with the reading systems of other countries. The priority is that the document functions in the same way both inside and outside the issuing State.

Facial image and fingerprints of the holder

According to the Regulation, verification must be based primarily on the holder’s facial image. Where necessary to confirm beyond doubt the authenticity of the document or the identity of the person, fingerprints may also be used. To this end, cards incorporate a secure storage medium containing a facial photograph and two fingerprints in interoperable digital formats.

Period of validity

As a general rule, national identity documents have a minimum validity of 5 years and a maximum of 10. This interval seeks to balance stability with periodic data updates.

Some adaptations are nevertheless provided for. For minors, validity may be shorter due to age-related physical changes. For older persons, Member States may extend the duration where reasonable.

What is the ICAO 9303 standard?

The requirement to incorporate machine-readable zones does not originate in Europe but in a technical framework that has been used for years in travel documents.

The ICAO 9303 standard is the international framework that establishes how passports, visas and identity cards must be designed so that they can be read automatically anywhere in the world. It is defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization in its Document 9303.

In essence, its aim is to ensure that a document issued by one country can be understood, verified and validated in another without the need for adaptations or interpretation.

This document defines general specifications applicable to all MRTDs (Machine Readable Travel Documents) and others specific to each type of document.

For identity cards covered by the Regulation, the specifications set out in Part 5 of ICAO Document 9303 apply. To achieve the highest possible level of standardisation, these documents are divided into two main areas: the machine-readable zone (MRZ) and the visual inspection zone (VIZ).

The machine-readable zone

The best-known expression of the ICAO standard is the Machine Readable Zone, or MRZ.

If you look at the lower part of your passport or the reverse of your national identity card, you will see several lines of uppercase alphanumeric characters separated by the symbol <. This strip is a structured encoding of the holder’s data.

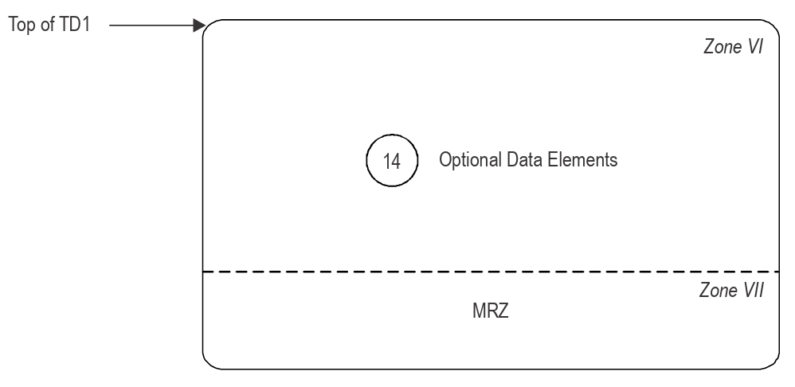

The reverse side of the DV1 also contains an optional data area (Zone VI). The configuration of Zone VII, the mandatory machine-readable zone, is shown below.

Figure 2. Data layout on the reverse side

Note. Reprinted from Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs) (p. 4), by International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 2021, Doc 9303.

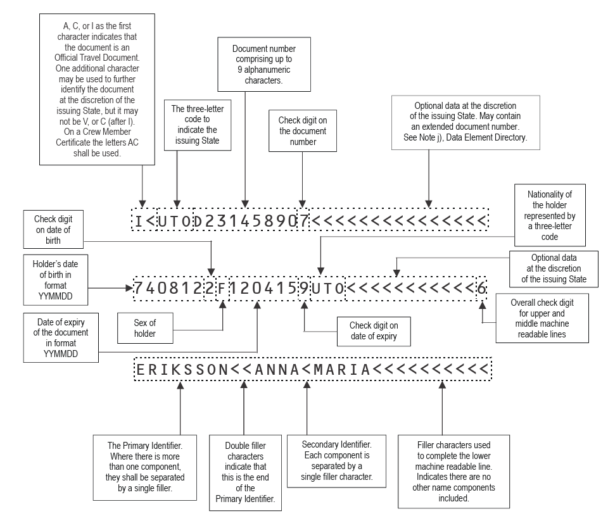

The MRZ has a standardised structure, and the position of text within it has a specific meaning. Some of the data it includes are:

- Document code

- Issuing country

- Document number

- Check digit

- Date of birth

- Sex

- Date of expiry

- Nationality

- Name

Figure 3. Data layout in the MRZ

Note. Reprinted from Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs), by International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 2021, Doc 9303.

It also introduces check digits or checksums to detect possible reading errors or manipulation. If someone alters a number or data field, the sequence no longer matches and the system identifies the document as fraudulent.

Thanks to this fixed structure, an optical reader can interpret the content regardless of the language of the document or the graphic design of the front. The system does not read as a person would; it simply knows that certain positions must contain certain data.

How MRZ reading works under the ICAO standard

The MRZ uses the OCR-B typeface designed to facilitate optical character recognition. This allows digital identity verification tools to capture the information automatically, extract it, interpret it according to the standardised structure and verify the check digits to ensure that the data have not been altered.

Visual inspection zone

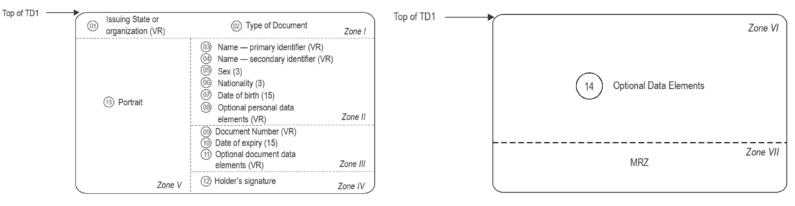

Document 9303 does not only define how data must be read by machines. The ICAO standard also establishes criteria for visual inspection (VIZ), including character type and size, line spacing, languages and the character set to be used in the visual zone. In the following image of the front and reverse of the document, according to the ICAO standard, the VIZ can be observed in Zones I to VI.

Figure 4. Data layout in the VIZ

Note. Adapted from Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs) (pp. 4–5), by International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), 2021, Doc 9303.

Why Europe is adopting the ICAO standard for national identity documents

The European Union has decided to strengthen the security of identity documents because adopting this technical framework is almost inevitable.

The ICAO standard is already used in passports and border controls worldwide, and the technological infrastructure is deployed in airports, ports and other border crossing points. Integrating national documents into this same ecosystem avoids the need to develop separate solutions and guarantees immediate compatibility.

The result is that a national identity document issued by any Member State can be read with the same devices that process international travel documents.

National identity thus becomes part of a global verification network aimed at tackling international crime, terrorism, illegal immigration and identity theft.

Rules for residence documents

Residence documents for EU citizens must include at least:

- The title of the document in the official language or languages of the issuing Member State and in at least one other official language of the European Union

- A reference stating that the document is issued on the basis of Directive 2004/38/EC

- The document number

- The holder’s full name

- Date of birth

- The information that must appear in registration certificates and in documents certifying permanent residence (Articles 8 and 19 of Directive 2004/38/EC)

- The authority issuing the document

- The two-letter code of the issuing country, printed in negative within a blue rectangle surrounded by twelve yellow stars (reverse side)

- Optional fingerprints

Residence cards for family members of EU citizens who are not nationals of a Member State must be issued in the common format established by EU legislation on residence permits (Regulation (EC) No 1030/2002 and its amendments).

These cards must be titled residence card or permanent residence card and must expressly indicate that they are issued to family members of Union citizens in accordance with Directive 2004/38/EC, using the prescribed standardised codes. Member States may add data for national use, but they must do so while respecting the data protection and processing requirements established in that European legislation.

Key dates for wihdrawal the documents

The regulation establishes a progressive timetable for the withdrawal of formats that do not meet the minimum standards or do not include an MRZ.

- 2026 (End of documents without machine-readable zones): From that moment onwards, documents that do not incorporate a machine-readable zone or that do not meet the basic security requirements will cease to be valid, even if they have not expired. This will mean the disappearance of the oldest models, especially paper ones.

- 2031 (General withdrawal of older formats): By then, all documents that do not fully comply with the new specifications must have been replaced. This date marks the end of the transitional period and all European documents are harmonised..

In Italy, the traditional Carta d’Identità cartacea, the paper identity document, has a set end date

On 3 August 2026 it will cease to be valid regardless of the expiry date printed on each document. It will not matter if it is formally still valid. For legal purposes, it will fall outside the system because it does not meet the new security standards required for identity and travel documents.

Millions of citizens are still using the paper version, so all of them will have to migrate to the new format before the established deadline.

The alternative will be the Carta d’Identità Elettronica or, failing that, the passport. The electronic card thus becomes the sole document for identification before the administration, carrying out procedures or accessing services.

The measure also affects Italian citizens residing abroad, who will have to arrange the replacement through their consulates.

Other European countries that have already left paper identity cards behind

Italy has not been the only country to retain paper formats.

Much of Europe has coexisted with identity documents in paper, plasticised card or laminated supports with minimal protection until relatively recently. These were legally valid credentials, but increasingly misaligned with the technical standards already required for TD3 documents or passports.

In Greece, for example, the national document until very recently remained a basic plasticised format, without a chip or electronic capabilities, which generated recurring criticism due to its limited resistance to fraud. The implementation of a more robust electronic card has recently begun.

Something similar occurred in Romania, where traditional laminated models have progressively given way to more secure digital versions.

Even countries such as France, which already used plastic cards, maintained until a few years ago documents without a chip or biometrics. The current carte nationale d’identité électronique is in fact a recent update.

By contrast, other States such as Germany, Spain or Belgium moved earlier and adopted electronic formats sooner.

Identity verification under the new European standard

The European landscape has therefore historically been uneven. What is changing now is that this diversity is no longer possible. With the new regulation, all documents are converging towards a single model.

This harmonisation has a direct consequence for public administrations, private companies and any organisation that needs to verify the identity of its users.

As mentioned previously, each country has issued documents with different formats, layouts and levels of security. This required verification processes to be adapted to multiple casuistries and exceptions. The technology existed, but documentary fragmentation made scalability more difficult.

With a common framework following the ICAO standard, this complexity is reduced.

Solutions such as MobbScan have been operating for years in heterogeneous environments, capable of processing both modern documents compatible with international standards and legacy documents or non-standardised formats. The difference is that, in a harmonised scenario, that verification can be simplified.

MobbScan makes it possible to automatically capture the information contained in identity documents and passports, read the MRZ, cross-check it with the visual zone or VIZ, verify the integrity of the document and compare the document photo with a real-time selfie, regardless of the country or format.

If you are looking for a solution capable of validating identity documents that follow the ICAO standard and that works with documents from different countries, typologies and characteristics, do not hesitate to contact us.

I am a curious mind with knowledge of laws, marketing, and business. A words alchemist, deeply in love with neuromarketing and copywriting, who helps Mobbeel to keep growing.

PRODUCT BROCHURE

Discover our identity verification solution

Verify your customers’ identities in seconds through ID document scanning and validation, and facial biometric matching with liveness detection.